- Home

- Art

Original art for sale

Shop original and limited edition art, directly from artists around the world.

Clear all

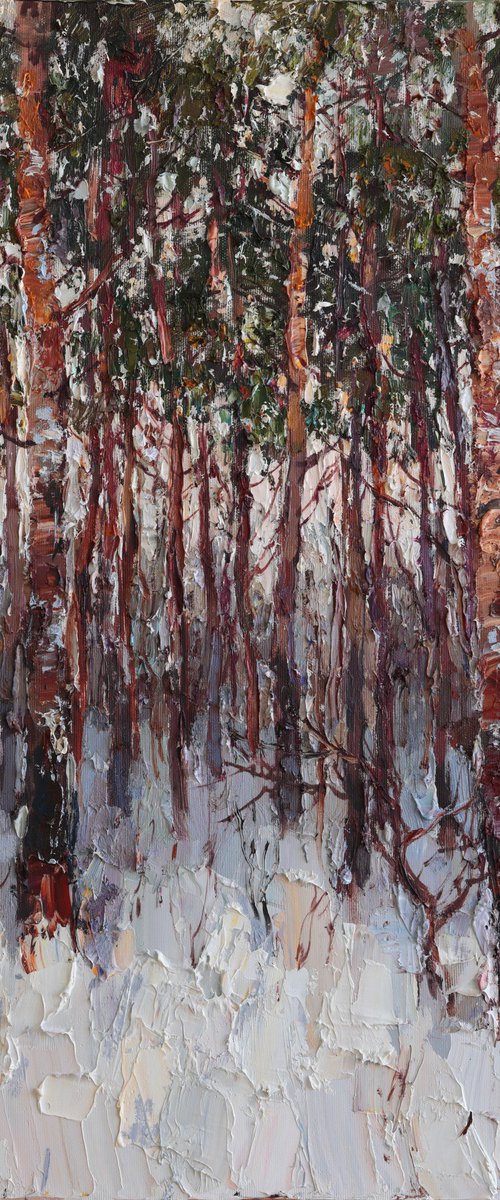

Mykhailo Novikov

Oil painting

100 x 70cm

£570

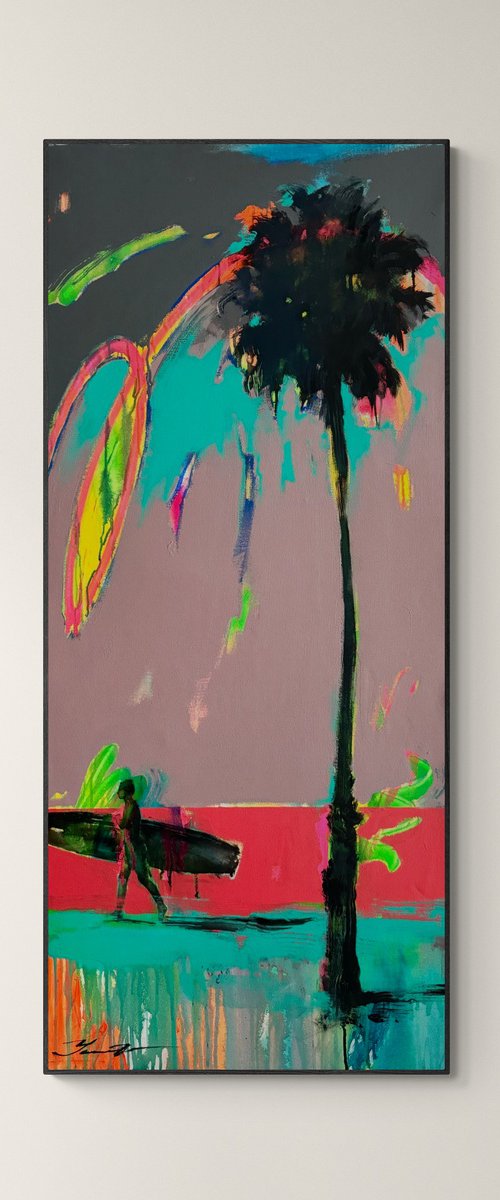

Paul Cheng

Acrylic painting

51 x 61cm

£585

Eva Volf

Oil painting

117 x 117cm

£2778

Andrej Ostapchuk

Oil painting

60 x 80cm

£595

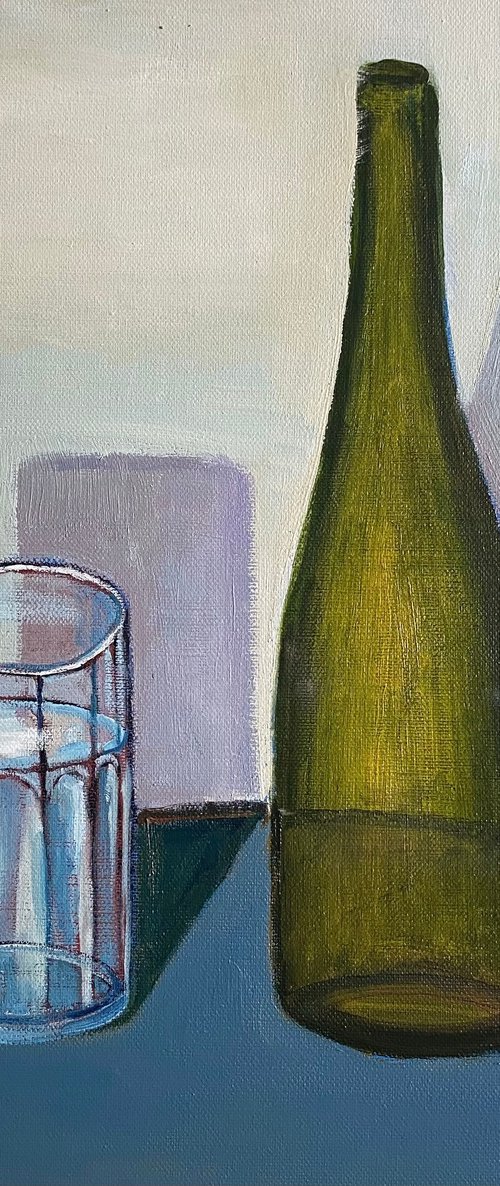

Ewa Czarniecka

Oil painting

30 x 25cm

£400

Anastasiia Valiulina

Oil painting

40 x 60cm

£740

Yaroslav Yasenev

Acrylic painting

56 x 128cm

£2100

Steven Page Prewitt

Oil painting

122 x 152cm

£3985

Guy Pickford

Oil painting

43 x 53cm

£220

Xuan Khanh Nguyen

Acrylic painting

60 x 50cm

£439

Lena Vylusk

Oil painting

50 x 70cm

£450

Nigel Sharman

Oil painting

46 x 46cm

£825