We’ve all heard of the names Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Picasso and Klimt. All of these men have contributed to the art world as we know it today, clearing the path for new and interesting artistic styles and concepts. But, we also know for every man celebrated and lauded, there were just as many women painting, sculpting, drawing and photographing quietly (and sometimes not so quietly) throughout history.

To celebrate International Women’s Day, we’re delving into the lives and inspirations of the women artists whose names aren’t as familiar as O’Keeffe’s, Kahlo’s, Maar’s and Kusama’s, but should be. And while this list of remarkable female artists certainly isn’t exhaustive, we’re sure you’ll discover a new name from history who’s just as impressive as their male counterparts.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803)

French painter, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, was born in the mid-18th century in Paris. Starting out using pastels, Adélaïde began exhibiting her work in 1774. Having not been accepted into any formal academy, she learned and trained in her craft by working in several artists’ studios.

After building her portfolio over 9 years to become an oil painter of full-scale portraiture, Adélaïde was admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1783 - a huge accomplishment considering around this time, Louis XVI had pronounced that the maximum number of women to be admitted to the academy at any given time was the huge and progressive number of… 4. It was here that she worked alongside fellow portrait artist, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun.

Adélaïde’s Self Portrait with Two Pupils (1785) is perhaps her most famous work, depicting a woman in front of her easel teaching her younger female pupils how to paint - a huge statement to make at the time (and potentially aimed at her mate, Louis?).

Throughout the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror toward the late 18th century, Adélaïde remained living in France but her work dissipated as artistic institutions were either shut down or began to prohibit women from becoming members. She died in 1803.

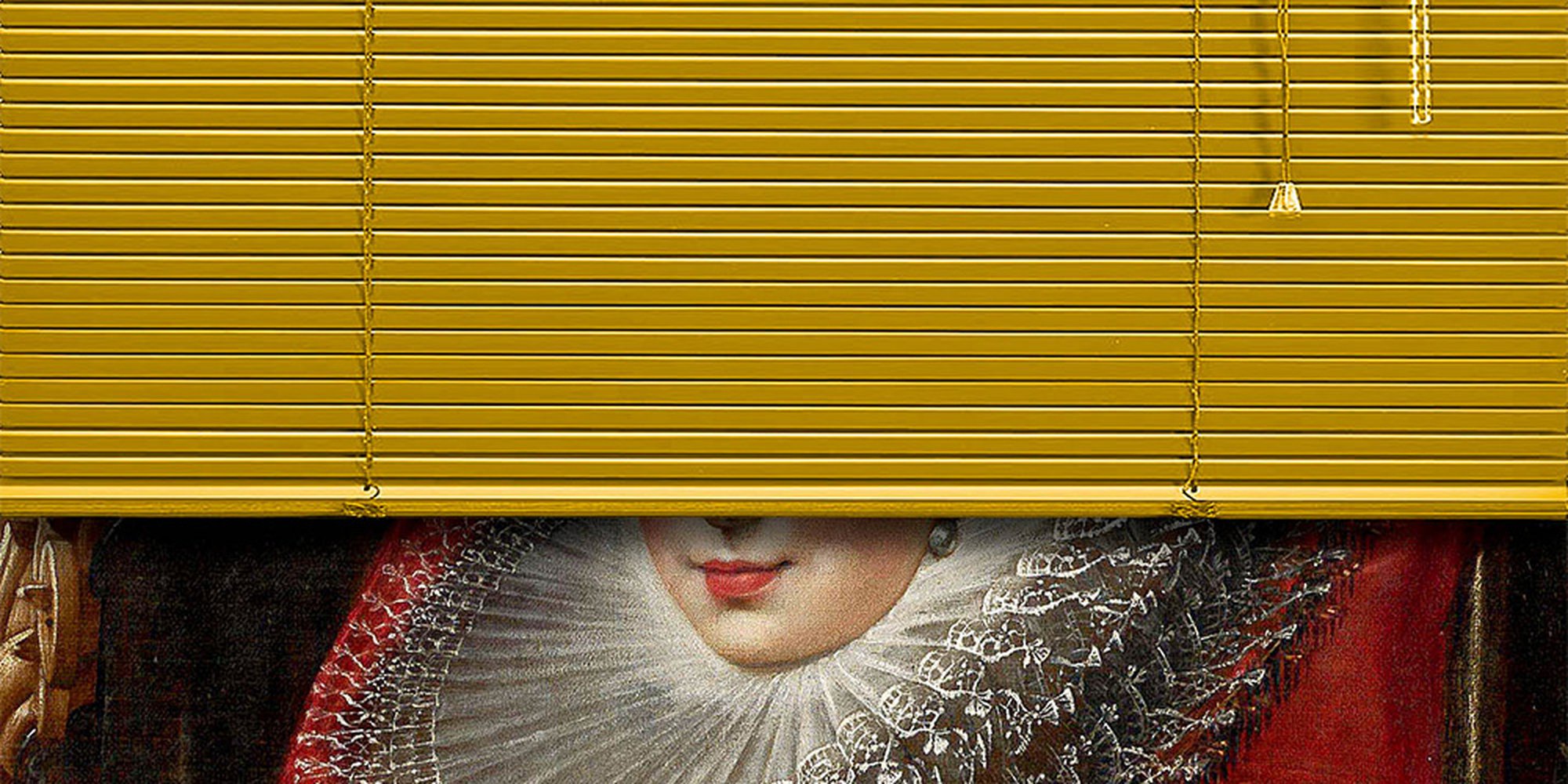

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842)

When we consider Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, it’s impossible not to also acknowledge her bravery, both as a highly successful female artist and French exile.

A contemporary of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Elisabeth was also born in Paris under the reign of Louis XVI. Unlike Adélaïde however, Elisabeth received early art training from her father, who encouraged her to pursue painting. By the time she turned 19 years old, Elisabeth’s work was gaining so much traction from the public that she had her materials confiscated - working as a professional without formal academy membership was a no-no. So were the times for women in art.

Elisabeth soon (luckily or unluckily, depending on how you view it) caught the attention of Queen Marie-Antoinette, who she went on to paint numerous portraits of. With Marie-Antoinette vouching for her, Elisabeth then joined Adélaïde at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1783.

During the Revolution, Elisabeth was forced to flee France in 1789, having been associated and tainted with the same brush as Marie-Antoinette. With her daughter, Julie, in tow, Elisabeth still managed to continue painting (while also raising her daughter as a single woman) and was commissioned by nobility in Italy, Austria, Russia and Germany. She was known to capture her subjects using influences from both the former Rococo style of painting and the newer, on-trend Neoclassicism style, leading her to become one of the most successful artists of the time, regardless of the fact she was a woman.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

Rosa Bonheur is a particularly interesting artist in history, as she challenged the idea of conventional standards and femininity within the 19th century art world.

Rosa was born in France in 1822 and like Elisabeth, followed in her father’s footsteps to become a painter. However, she was more interested in painting animals, choosing to observe directly from nature - painting en plein air, a relatively unheard of concept before the rise of Impressionism in the mid-to-late 19th century - and in local slaughterhouses to improve her anatomical knowledge. She especially loved horses and her 1853 piece, The Horse Fair, pushed Rosa to international fame.

Many critics of Rosa’s (no guesses as to their gender) described her as painting “like a man”. She wore her hair short, smoked tobacco and lived with a female companion. She wasn’t one to mince her words either, saying “as far as males go, I only like the bulls I paint” (National Gallery, UK).

At the age of 43, Rosa was the first ever female artist to be awarded the Legion of Honour - a feat that seems remarkable, considering the hurdles she overcame to get there.

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944)

Years after her death, Hilma af Klint was exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum, where she was recognised as one of the pioneers of abstract art. And guess what? She produced her abstracts years before Kandinsky and Malevich.

Hilma was born in Sweden and at the age of 25, graduated from Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Hilma lived and worked during a time of unprecedented social change and scientific advancement. It is here that she looked to theosophy (a belief system that blended both religion and philosophy) to try to understand the fast-changing world around her.

And while male artists like Kandinsky sold themselves as artistic geniuses of the time, Hilma worked in the background, quietly producing hundreds of pieces she was adamant were not to be shown until well after her death. This group of paintings were named The Paintings for the Temple, which explored themes surrounding traditional creation narratives and more modern evolutionary theories.

Hilma’s body of work was indeed shown in a temple - in 2018, at the Guggenheim Museum, 74 years after her death - which remains the most attended exhibition at the Guggenheim, ever.

Augusta Savage (1892-1962)

If it wasn’t hard enough identifying as a woman in the early 20th century, Augusta Savage was also an African-American sculptor, navigating America’s racial segregation and Jim Crow laws.

Born in Florida, Augusta moved to New York in 1921 to study art at Copper Union. After two years in New York, Augusta then applied for a summer art program but was rejected because of her race. Following her rejection and spurred on by her fight for equality, Augusta began receiving commissions and sculpted W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey and William Pickens.

In 1929, Augusta’s sculpture of a child from Harlem prompted a scholarship at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and in 1934, she became the first African-American artist to be elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. A remarkable feat considering she’d been rejected from the summer art program just under a decade prior.

Augusta dedicated her life to activism, fighting for equal rights in the arts. She also taught her craft and launched the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, which eventually became the Harlem Community Art Centre, a place that celebrated and supported young Black artists, including Jacob Lawrence.

Image credit: Slasky